What is toughness, anyway?

When my father was diagnosed with cancer in 2008, I wrote a blog article titled, “Tough.” But there’s a better word for what I was seeing in the man.

“My dad is tough,” the blog begins. “Where others back away from the unknown, he has nurtured a life of challenge.” I go on to laud Dad’s toils and triumphs in running, climbing, and mountaineering—and there were many—as evidence of toughness.

Today—the passing of both my father and my own alcoholic self behind me—I’d choose a different word for the ineffable something needed to thrive in a world that seems to ask for stoic suppression. Vulnerability.

What I saw in my dad in 2008 was softness. He made amends for the shrapnel of a life spent striving. He cried. Told his family he loved us desperately. Desperately.

I wonder; why do so many people wait until death knocks let their guards down?

I waited, too.

Seattle, 1998: I’m sanding the rusty roof of a ‘64 Chevy procured with my second semester student loan check. There’s rockabilly on the radio and a 24-ounce Pabst within reach. I feel distinctly, “This is man stuff. I’m doing it. I’m tough.”

A decade later—soon after Dad got his diagnosis—I pick up running and immediately set a marathon goal. My running is meant to comfort the old man; to mirror his toughness back to him, and to give us fodder for four-beer lunches.

Every version of “tough me” had a beer in hand, pushing down my gentle nature in service of a harder-edged caricature—a composite of all the tough guys I’d ever idolized. Gangster me with a forty-ounce. Hot rod me with a tall can. Marathoner me with a double-IPA.

All these Mikes were honest to a degree, as honest as I was equipped to be. I still love hot rods and hip hop, by the way. But constructing my identity in the direction of external influences and expectations tended to get me into trouble.

By 2020, I’d lost the thread. Booze had turned on me and threatened to take running away altogether. In the ultimate irony, rejecting my own softness brought me to my knees. I nearly toughed myself to death.

I blame Rod Dixon (not really).

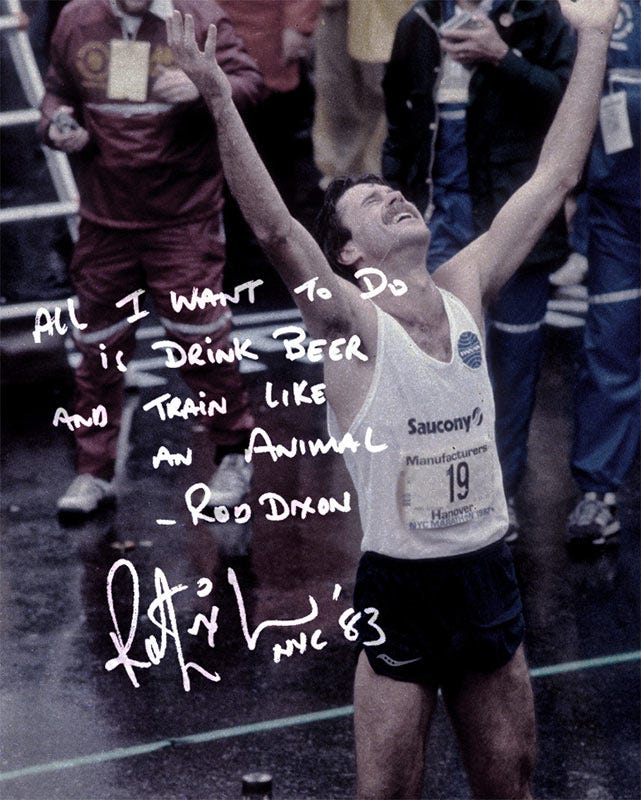

If you were around running in the eighties, you know the hard partying, hard running cliche. This half-truth is embodied in a “remember the good times” Instagram post from Saucony in late 2023:

Rod Dixon, man’s man. Slamming beers by night, laying waste to the competition by day. This was the competitive environment, and it set the toughness bar for people like my dad—who, in turn, passed it to me. Thanks, Rod Dixon.

That approach to life and training is attainable by few, sustainable by even fewer. Mercifully, for our collective liver health, the prevailing running ethos (and marketing mandate) has evolved to more than macho displays of superiority.

In 2024 and beyond—save for the occasional Saucony-style throwback—we are free to consider how different interpretations of toughness fit into our lives.

A Baseline

In simple terms, toughness describes the various ways people meet life’s burdens.

We can stiffen and try to push problems away through sheer force of will. We can soften and flow through, trusting our capacity to adapt. Or—and, spoiler alert, this is where the article’s headed—we can find a combination of the two that suits.

External Toughness: Push

Humans are signaling all the time. To find our tribes and keep incompatible or dangerous people at bay, we armor up. We wear costumes—sometimes hand-me-downs, occasionally original creations—and we signal.

External toughness is performative like that. “Acknowledge my strength,” it says. Because its roots are in the expectations of others, external toughness is about demonstrating expertise, sometimes through exaggerated displays. The score is kept by relentless comparison and seeking of approval.

The slippery slope of external toughness is that it becomes internalized as the only way to think about and measure ourselves. Our world turns black and white—we succeed or fail, win or lose—with no gradient between.

Fragile self-esteem and its evil twin, chest-thumping pride enter the chat.

A proud man is always looking down on things and people; and, of course, as long as you are looking down, you cannot see something that is above you.

- C.S. Lewis (Mere Christianity)

Once excessive pride is in the picture, things shift from pursuing approval of oneself, to judgment and envy of others. This is the yucky side of external toughness: A dissolution of kindness.

It’s a constricted world, suspicious of novelty and resistant to change. Here, the externally tough guy gets stuck in narrow or ill-defined worldviews, to which everyone around him is expected to subscribe. When things don’t go to plan, he becomes some combination of angry, mean, depressed, and addicted.

Internal Toughness: Flow

As a kid, I was free to explore and validate things for myself—to think. When teenage me borrowed the costume of the inner city and joined a “gang” in my small Montana hometown, I hadn’t stopped thinking (though it might have appeared that way). I was just deriving more strength from others than from my own inner world.

So it goes with soft-spoken internal toughness—forever playing second fiddle to its boisterous cousin, because we’re social beings and we can’t help it.

If external toughness demonstrates, then internal toughness considers. It’s the voice of humility that asks, “What is this situation trying to teach me?” Internal toughness compels curiosity and continual growth. It builds our strength slowly, one successfully-met burden at a time.

Whereas people showing external toughness push against difficulty (or at least try to appear unaffected), those practicing internal toughness accept and move through it. They are masters of the moment, understanding that change can’t be willed away, and instead believing in their own ability to adjust.

The contrast of willpower versus belief is, as I see it, the key difference between internal and external toughness.

Willing is wanting, a top-down phenomenon. The mind tries to make you trust you can realize a goal. Believing is bottom-up. Through practice, you learn what you can do.

- Matt Fitzgerald (The Mind-Body Method of Running By Feel)

So one is bad and the other is good?

It’s not that simple, is it? We’ve all been in situations that demand armoring up with external toughness. And, while unconditional self-acceptance is an admirable aspiration, few can exist insulated from external influence.

In the context of sport, it’s worth considering that some measure of Rod Dixon-esque toughness (minus the boozing, maybe) is even required to reach our potential.

Five-time U.S. National Champion runner-philosopher Sabrina Little wrote a knockout piece on this very thing, which you should go read now (but please come back): Performance Enhancing Vices

From that article:

Pride’s epistemic [cognitive] error is unlikely to enhance performance. Imagine the runner who perceives her abilities as far greater than they are. She may start a race at a pace commensurate with her projections, then crash and burn. To succeed in sports, we need high levels of ability, but we also need to perceive our limits accurately.

However, pride’s error of valuing is likely to enhance performance. The sportsperson who over-values themself is inclined to inordinately strive for greatness and to be engaged in the activity of reputation protection. And pride’s greatest secret is that it is always under threat. It needs to prove that it is the best. This provides ample motivation to dig deep.

So, it’s not a question of good and bad, but of finding the mix of internal and external toughness that advances our goals in life and running.

Toward Antifragility

There’s a word for the individualized blend of toughness that allows people to bend, but not break in the face of change and difficulty: Resilience.

Imagine hundred-pound steel balls, dropped from a height to two different surfaces.

One is concrete. Rigid and able to withstand a great deal, but no match for this challenge. It fractures. This is external toughness.

The other is a trampoline. Structured yet flexible, it yields and rebounds, returning the ball to the air again and again, until it eventually settles. This is resilience.

Between the two, we want to be more like a trampoline. But a lifetime of trials leaves a lot of balls on the surface (snicker), eventually affecting its ability to rebound.

Imagine a third option: A self-healing—no, self-strengthening—material that actually improves with adversity. This is antifragility, crescendo of the toughness concerto.

We have a good biological proxy for such a self-strengthening super-material: Muscle.

Growing muscle requires exposure to challenges (stress), in a consistent program that equally values recovery (rest), and gets more difficult over time (progression). The antifragile brand of toughness works this way, too. We face burdens with open hearts, consider what the adversity is teaching us, and rebound stronger.

What’s a word for exposure to harm or failure that leads to adaptation and growth?

Vulnerability.

My friends, vulnerability is toughness, too.

The Finish Line

I began this article with a favorite book close by, Steve Magness’ Do Hard Things. I underlined a couple things and never picked it up again. Thinking more about its theme, “what we get wrong about resilience,” I decided to go this one alone.

Right and wrong exist together, on a spectrum. Integration of different viewpoints is what creates truth. Your truth is different than mine, but the same in that it’s meant to change and evolve. But where do we start?

Confidence is simply a way of moving through the world with a correct view of your strengths and vulnerabilities, in order to face the possible with unstoried willingness.

- Maria Popova (Impostor Syndrome and the True Measure of Success)

A correct view. That’s it. Not self-aggrandizing or the more common self-diminishing. Just an honest assessment. Start there.

My dad seemed to have finally understood this when he went calmly to the mountains one last time. But you don’t have to wait. Start now.

Consider how toughness was modeled to you, and whether that fits with who you are and who you’re becoming. Notice how toughness is marketed and sold, and resist stuff that doesn’t align.

Be open to transformation.

Run lightly,

-mike

Running Lightly is building a community interested in the soul beneath the surface.

The real toughness is showing your weakness. What a beautiful take! ❤️

What a wonderful look at what toughness really is. Feel like my mindset shifted a little bit through such a short time reading this one. Thank you for sharing and being vulnerable.